Familiarization – Silent to Surfaced

Uncertainty and the feelings of a loss of control over my life, drive a great deal of anxiety and even despair at times. I’m learning that I can begin to take control of the feelings of uncertainty that lead to this kind of despair, if I am willing to make inward journeys to recover the subconscious thoughts that actually fuel these feelings. In my life, I am increasingly motivated to invest time in these inward explorations. I can see that understanding myself and my behaviors lies at the heart of bringing harmony to my relationships, balance to my health and fulfillment in my work. While these are noble goals, I can also see that to not address the inner sources of my anxiety is downright dangerous on all of those fronts.

At its core, anxiety is fueled by thoughts. Thoughts and actions are the result of how our brain is currently wired. Not all thoughts are created equally though. Some thoughts are silent, persistent, disturbing and controlling. Like landmines, these thoughts come with a hidden charge of unrequested and destructive energy. I’ve learned that the first step in bringing anxiety under my control involves learning how and where to look for these silent destructive thoughts.

Having struggled with these types of feeling for many years, I have developed a way of thinking about the them that breaks down into three incremental steps or phases. The first phase can be described as familiarization. Behavioral and scientific advances in the past 10 years, have shined new light on how spending time with anxious feeling to become familiar with how they are making me feel, places me on the right path. On this path, I can gain deep insights into how to eliminate the forces that give rise to the feelings of uncertainty and a loss of control over my life as they arise.

Familiarization – Silent to Surfaced

Previously, traumatic episodes such as sexual or physical abuse during adolescence were considered worthy of intense investigation as a source of personal healing. Recent studies and advances in brain imaging technology demonstrate that a much broader range of adverse events, such as financial hardship, divorce, chronic physical or emotional illness or death of a parent, date sexual assault, learning impairments, and chronic bullying by a sibling should be investigated as well, particularly when these experiences occur in the years leading up to and during a person’s adolescence.

As events like these cover a much broader range of experiences, they can occur with more regularity in our adolescence and in a much larger percentage of the population. When these experiences occur at the same time that our brains are rapidly structuring during our adolescent years, they almost invariably leave the subconscious thoughts that provide the broad neural pathways that channel anxiety in our adult lives.

My own feelings of insignificance that result from what I perceive as someone treating me with a lack of appreciation, emerged as a good starting point for isolating these types of silent thoughts. I understood that with anxiety being a genetic trait, that one or both of my parents had suffered from anxiety issues when I was growing up. So the connection wasn’t difficult to isolate. While I knew that they loved me and had always done their best, I recognized their malady took away their ability to be aware of my general well-being and safety for extended periods. I could tell that these feelings had left a channel for anxiety in my adult life. Even decades later, when events occur that feel similar to the feelings from the past of not being watched over or cared about, I tend to become far more unsettled than someone who didn’t have this kind of experience.

I felt confident that I had apprehended a prime incendiary-device-planting suspect. I felt as though I was hot on the trail of finding more of these bandits, so I kept looking and listening. It wasn’t hard to see that my chronic stress regarding a lack of financial security was related to having suffered through a lot of family financial ups and extended downs during my adolescence. The same financial conditions that are simply a cause for concern for someone else, like having enough money to pay the bills, have always been a deep cause of chronic stress for me. Another bandit had been apprehended and detained for questioning. Bringing that one in seemed a little too easy.

Though my efforts were paying off, I sensed that I hadn’t brought up the ringleader. So I decided to keep going. For those who have experienced multiple adverse events during their adolescence, the task of confronting the silent thoughts that endure, often feels insurmountable. I recently realized that these types of thoughts act together to ratchet up anxiety and distort my ability to determine my own emotional needs in my present life. My failed attempts to address my fears of financial hardship by becoming a master of household financial budgeting began to make much more sense. Another character always seemed to be waiting in the shadows to ambush me from behind the bushes. The lights of science had now brought this shadowy figure into full view though.

Chronic adolescent events, like suffering physical and emotional abuse from a sibling, can create an overarching inner menace that works in tandem with the other silent thoughts. I could now see clearly that the anxiety that was present during my teen years caused by my older sibling’s constantly aggressive behavior caused me to carry tensions that were unrelenting as an adult. I could also now see that these tensions ratcheted up considerably when I was working to address my fears of financial hardship and needed cooperation from another person. Recognizing these inner villains and, most importantly, how they worked together, gave me the sense that I was possibly close to the breakthrough I had been searching most of my adult life for. Go science!

After apprehending these thoughts, the step was to prevent them from slipping back beneath the surface. I sensed this had to be done to allow me to associate these bad guys’ blasts-from-the-past, with the anxiety I was experiencing in my adult life. To force these thoughts to go from silent to surfaced, and to get them to remain there, I formulated and asked myself questions when I was experiencing anxiety that were tailored to the types of experiences I had as an adolescent. I asked myself “am I feeling lost and alone and like no one cares, like when I was younger?” Or “are these feelings taking me back to a time when I was a teenager, when I worried about how we were going to be able to keep the house or buy groceries?” And “does this feel like when I was being bullied and constantly sabotaged when I was growing up?” Answering “yes” to these types of well-formulated questions helped me latch on to those silent thoughts and keep them from slipping back into the darkness after they had instigated their ruckus.

I began to view coming to terms with these deeply unsettling thoughts as a familiarization stage. In this stage, I reacquainted with them so I could recognize how powerful their blasts actually were. My anxiety, as it turned out, seemed to have little to do with what was going on in the present. So the potential effectiveness of addressing these thoughts once and for all was becoming increasingly hard to neglect. Coaxing these thoughts to remain surfaced didn’t take place overnight and always left me feeling a bit unsettled sometimes even a little nauseous. Those feelings tended to fade pretty quickly though. And as I was gaining familiarity with them, science again stepped in to help me make something positive from these unpleasant yet intriguing feelings.

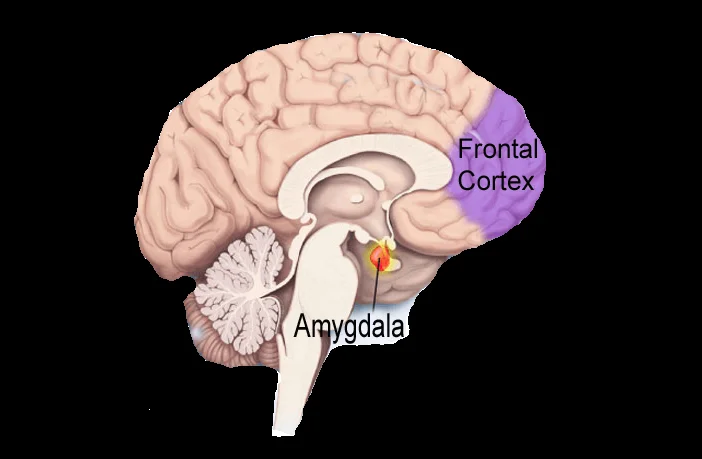

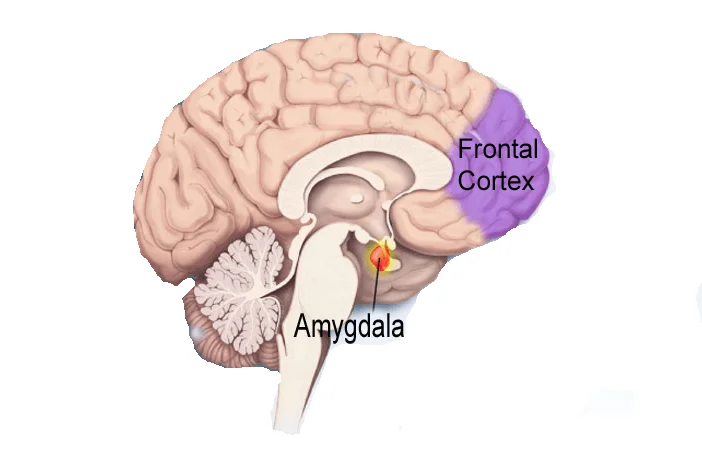

Scientific advances of the past ten years have revealed that a key area of the brain, the frontal cortex, can be forcibly rewired to stop the anxiety that comes from these silent thoughts. To help visualize the target area for changes, make a fist with your thumb inside of your fingers. The outer part of your fingers resembles the frontal cortex. The frontal cortex occupies the space behind your forehead and is quite large compared to the other parts of the brain. Acting as our executive decision maker, the frontal cortex orchestrates the other subcomponents of the brain to provide responses to how we think, feel and behave. The frontal cortex works in terms of seconds and minutes, as it assimilates the responses from the different parts of the brain into a response.

The frontal cortex has a pushy partner, the amygdala, that stores how we feel about past experiences. In the fist example, your amygdala would be your thumb tucked deeply inside the brain. The amygdala provides the historical context to silently render a decision regarding whether or not a current situation is safe or unsafe. As our amygdala’s job is to alert us to imminent physical dangers that could immediately kill us, it has evolved to provide a response to the frontal cortex in milliseconds.

In functional responses, the amygdala weighs in to assist the frontal cortex in making a rational decision regarding the safety level of a current situation. However, in situations where adolescent adversity impacted the brain’s development, the amygdala has been wired with an up-signal to the alert frontal cortex; however, the frontal cortex does not have a corresponding down signal to let amygdala know that everything is ok. This disconnect occurs because the Frontal Cortex develops toward the far end of adolescence. In these situations, the unchecked amygdala reaction, ignites a biochemical charge to react to a physical threat. In today’s emotionally driven world, these biochemicals instead result in the tension that fuels anxiety.

After learning that the frontal cortex could be further developed long after adolescence has concluded, I decided to take a shot at scripting new thoughts to establish the down signals to let my amygdala know that today’s challenges are emotional and not physical. With these thoughts, perhaps my frontal cortex could hear early signals from my amygdala and let it know that I don’t need all of the fuel to fight off a physical threat. The pyrotechnics can stop.